|

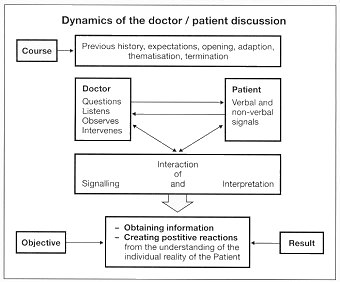

Dynamics of the doctor/patient

discussion

The structured interview is

most likely to be favourable if the dynamics follow a regulated course

(Figure).

In many cases, there is a

previous history. In a situation of expectation, the most difficult

part is at the opening of the discussion. Then follows a mutual adaptive

phase. The objective of the discussion is a definition of the

theme,

and the discussion is ended by a termination. The course of the

discussion is the result of interaction between the two partners. The doctor

is responsible for asking questions empathetically, for

listening

actively and for watching for all non-verbal signals from the

patient. His questions are aimed to obtain information which elucidates

the individual reality of the patient, and when necessary, to steer the

discussion by intervention.

The patient acts or reacts

during the discussion, by verbal and nonverbal communications, but

can also "answer" with silence. The doctor interprets these signals

from the patient as a "participating observer". In this way he builds up

a picture of the patient, his personality, and the possible conscious and

unconscious motives in a conflict situation.

The patient acts or reacts

during the discussion, by verbal and nonverbal communications, but

can also "answer" with silence. The doctor interprets these signals

from the patient as a "participating observer". In this way he builds up

a picture of the patient, his personality, and the possible conscious and

unconscious motives in a conflict situation.

Mitscherlich termed the doctor-patient

discussion as "interaction of signals and their interpretation". From the

interpretation, the patient receives the impression: "Here is somebody

who has found out about me and does not shy away from discovering the truth

with me".

| top |

|

|

History before the

(initial) discussion

The first doctor-patient dialogue

does not usually arise from a vacuum. Even the means by which the consultation

has come about (appointment, ward round, home visit, accident) play a decisive

role in the initial discussion. The doctor has information from the patient

himself, from relatives or from previous examinations. This means that

certain presumptions are possible before the discussion, although

these are subject to all of the dangers of prejudgment. If the patient

has a choice, the fact that he has chosen one particular doctor is significant.

The motives for a choice of doctor can be very variable; previous experience,

particular competence, reputation, age (sex) or simply because he is easily

available. Whether he was referred by another doctor, if he came of his

own accord, and if he comes alone or accompanied by relatives are also

relevant.

| top |

|

|

Opening phase

The discussion is opened after

an expectant phase. The importance of a good opening for discussion

is dealt with in the chapter on the initiation of discussion  .

Studies have shown that the relationship between doctor and patient is

often established and structured during the first interview, and that this

markedly determines the course of further discussions. .

Studies have shown that the relationship between doctor and patient is

often established and structured during the first interview, and that this

markedly determines the course of further discussions.

| top |

|

|

Adaptation phase/thematization

The discussion partners agree

"to accept each other" as discussion partners during the adaptation phase,

and develop a common psychical field.

Only now is it possible to

develop

a theme. Here the doctor has two important tasks; the first is to recognize

the true subject of the discussion, and secondly to steer the discussion

so that working through this subject is as effective as possible.

|

Both tasks are practically

impossible if the individual reality of the patient remains undetermined.

|

|

| top |

|

|

Closing (termination)

The discussion should not be

broken off at random, but should be terminated according to the particular

dynamics of the course of the discussion. The length of the discussion

depends on the acuteness of the situation, the subject under discussion,

the extent to which both doctor and patient can manage, on the course of

the discussion itself, as well as on the time available. A discussion time

of more than 45 minutes will only be possible or useful in exceptional

cases.

Ideally the discussion should

be ended when the primary subject is closed, or has been taken far enough.

The discussion should be terminated if the patient shows signs of tiredness

or excessive stress, if acute resistance arises which cannot easily be

resolved, or if the discussion gets into a cul-de-sac. There should always

be a review or preliminary review. The patient should also always be given

the opportunity to put further questions. Finally, the form of further

contact between doctor and patient should be agreed.

One phenomenon which arises

at the end of a discussion should be dealt with in more detail. Often patients

are able to mention the subject that is really important to them only when

the doctor is signaling the end of the discussion. The explanation is that

the patient develops a strong defensive tendency during the conversation,

which can only be broken down when, as the end of the discussion is approaching,

he anticipates that he will not be able to discuss these points at all.

This means that questions posed at the end of a discussion or points thrown

into discussion here, can really have a very great significance.

| top |

|

|

Technical aspects

In order that a discussion can

begin at all, it is necessary that the patient is able and ready to

speak, and the general situation is not unfavourable to the discussion.

Patients who make an appointment

and come to a surgery or practice agree to come at a certain time themselves.

On the other hand, the time of the visit of a doctor to the patient in

hospital is dictated by the requirements of the doctor. It therefore

has to be assessed if the patient is able to take part in a discussion

at a particular time, and this is not prevented by possible symptoms, pain,

hunger, thirst (being prepared for investigations), exhaustion or uncomfortable

positioning.

Problems also arise with

discussion during an examination. Occasionally, discussion can be

helped by closer physical contact during an investigation (ultrasound,

for example). It is very unfortunate when a good discussion is interrupted

by a physical examination, and the patient is left wondering whether or

not he will have an opportunity to discuss this subject again.

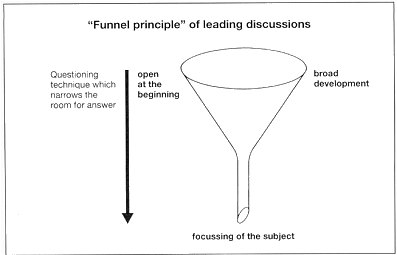

Opening of the interview

and further steering of the discussion should follow the so-called funnel

technique (Figure).

The method of an open introduction

with a broad unfolding is appropriate. Further questioning runs on sequential

principle. Initially the patient is allowed the largest amount of room

in which he can formulate his answers. As the discussion advances, the

contents of his answers are made more precise and clearer by decreasing

the room left for responses. This achieves a focusing of the subject

matter.

As regards the questioning

technique, the start of the discussion is accompanied by open questions

("How do you feel?", "What mood are you in?"). There are more answers that

can be given to the question: "How are you getting on?" than to the closed

question "Are things okay?" The information which is obtained is examined

more precisely by the use of an increasing proportion of closed questions.

In this way the subject is brought more and more within boundaries.

As this proceeds directive questions can be interjected, which serve

to plumb certain points ("Can you tell me more about the course of the

first attack?").

As regards the questioning

technique, the start of the discussion is accompanied by open questions

("How do you feel?", "What mood are you in?"). There are more answers that

can be given to the question: "How are you getting on?" than to the closed

question "Are things okay?" The information which is obtained is examined

more precisely by the use of an increasing proportion of closed questions.

In this way the subject is brought more and more within boundaries.

As this proceeds directive questions can be interjected, which serve

to plumb certain points ("Can you tell me more about the course of the

first attack?").

The doctor should anticipate

the patient's manner of telling his story. This depends partly on

the subject and its subjective importance for the patient, and partly on

his personality structure and character. Enough time must be available

for the discussion if details of the life history of the patient need to

be discussed.

Those who are "long-winded"

can pose a particular problem. In order to intervene, the doctor must determine

why

the patient behaves in this way. There are two main reasons. One is that

some people have a natural tendency to speak associatively. This means

that they find it difficult to stay with the point under discussion, and

what they say depends on the immediate situation or key-word which crops

up. With these people, intervention with directive and closed questions

is usually effective.

More problems are raised

in the second type of long-windedness, in which the same subject crops

up continually. Often this behaviour hides the patient's concern that he

will not be understood. Due to this, he attempts to ensure understanding

by continually repeating himself. In these cases, the following options

for intervention are available. Firstly the patient can be given strong

clear signals that his request has been understood. This can be achieved

verbally ("I am convinced that I now completely understand your problem"),

by the use of a series of questions which convince him that he has been

understood, or by using "echoing" questions ("This groin pain only happens

when you have eaten a lot of fibre?"). Another possibility is to choose

a single point as soon as convenient and go into it in detail as there

is usually less to discuss "in depth" than superficially.

A complete chapter has been

devoted to active listening  as this is the most important but also the most difficult ability for leading

discussion. The art of active listening does not only apply to what

the other is recounting, but also how he saying it and what he

does not tell.

as this is the most important but also the most difficult ability for leading

discussion. The art of active listening does not only apply to what

the other is recounting, but also how he saying it and what he

does not tell.

Meerwein points out the doctor

should also ask himself, whilst listening actively, what is happening

to him:

| • |

What

mood is the patient putting me into? |

| • |

Am I speaking

too much, too little or too impulsively? |

| • |

Am I free to

speak or inhibited by this patient? |

| • |

Do I really want

to see this patient again, or do I hope that he will never appear again? |

In other words, the doctor

must be prepared to listen not only to the patient but also to himself.

However, leading a discussion

is not limited to listening and questioning. It is necessary for the doctor

to repeatedly intervene in the conversation. One reason for intervention

can be that the course of the discussion is heading in the wrong direction,

or that it appears useless. At this point, it is helpful to introduce a

fresh, more attractive subject into the discussion in order to regain an

interactive pattern. A further reason for intervention can be to head-off

rising anxiety on the part of the patient (see chapter on anxiety  ). ).

Unwillingness to speak

may indicate defensiveness, which again requires intervention. However

the initial step is to confirm whether or not this is really defensive

behaviour. Although a break in the discussion may be interpreted as "refusal

to speak", it may in fact be a pause for decision or working through of

a point (see chapter on the pause in discussion  ). ).

If it appears from the "offer

of disease" and the preceding discussion that a conflict situation is at

the root of the physical symptoms, certain key questions serve to

elucidate the problem. Basically, a spontaneous exposure of the

conflict and working through it occurs much too infrequently in daily practice.

The grounds for this is that the patient is not really conscious of the

conflict and the doctor is not really prepared go into it. Studies from

the Heidelberg psychosomatic clinic showed that out of 100 patients referred

to the clinic, only 2 to 5 had really developed a truly conscious appreciation

of the conflicts (De Boor and Künzler). Guyotat could show that, on

the other hand, only 10 out of 75 doctors actively approached the conflicts

in their patients.

An important key question

which brings the internal conflicts into consciousness is to ask

the patient what he himself thinks are the reasons for his illness.

Von Weizsäcker formulated this question in the following way: "What

do you yourself believe to be the cause of your illness?". Meerwein recommends

the following question: "Why do you think that you are ill?". A further

aid can be to ask the patient for his own suggestions for treatment for

his illness.

It can also be important

to question, when it is clear than the patient's explanation has left "omissions

and loop-holes". Freud points out that one should "approach material at

deeper levels behind these weak points". Such holes and omissions can for

example concern certain people around the patient or his sexual life.

Nevertheless it would be

a mistake to mention conflicts too early in the discussion,

and to refer to the connection with physical symptoms. The patient does

not usually come to the doctor either aware of internal conflicts or with

the willingness to face these conflicts in discussion. When asked if they

would be prepared to speak to their doctor about personal problems, if

these had nothing to do with their illness, 73% replied "no", and only

22% "yes" (Delay and Pichot).

The basic rule of structuring

and intervention in discussion between doctor and patients has been

explained by Meerwein as follows: "None of these suggestions for intervention

in the course of discussion should deviate from the basic principle that

it is associations of the patient that define the discussion and not the

questions posed by the doctor. The questions and intervention of the doctor

arise when rationalization, omissions, contradictions, statements suggesting

anxiety and defensiveness, confrontation against the doctor and similar

forms of behaviour, influence or inhibit the development of the discussion.

The doctor needs to recognize these difficulties for what they are, and

to use them for understanding more of the illness". The final step in the

consultation interview is to establish a diagnosis and if necessary

its interpretation. The interpretation "reveals illness as being

not just a physical phenomenon but a crisis in human relationship - a conflict.

If correct and presented in a way acceptable to the patient, its result

is insight and benefit" (Meerwein). The interpretation allows worries and

uncertainties to rise to the surface, and to be put into words. This reduces

anxiety "as we rise above what we can express in words" (Nietzsche).

It can be difficult to make

a diagnosis, but even more difficult to give it an interpretation.

Meerwein lists rules which should be applied to every discussion

between doctor and patient, in which not only the diagnosis, but also the

interpretation

of the disease is required:

| • |

The

interpretation should extrapolate from what the patient himself expressed.

Therefore the patient's words, and not lofty language, should be

used. |

| • |

Interpretations

which under certain circumstances could hurt the patient should be avoided. |

| • |

The interpretation

of external conflicts should precede the interpretation of internal

conflict. Inner conflicts are rarely verbalized in conversation with doctors,

if the patient does not raise them himself. |

| • |

The interpretation is the

doctor's service, with which he compensates the patient's willingness

to converse. It encourages and reinforces the understanding

that the patient has of himself. As a result of it, the patient feels understood

and supported. This is where its therapeutic function resides. |

| top |

|

|

The closing of the discussion

Many discussions in daily clinical

practice end as they started: unstructured and unsystematic. The end of

the conversation is far more likely to be caused by external factors (such

as situations in discussion or time-pressure) than by logical and psychological

dynamics. Nevertheless, the termination of the discussion is just as essential

a constituent as the other phases in discussion. No business discussion

about a purchase or contract would end without a clearly-defined termination.

Many discussions are "crowned" by the termination.

The end of the discussion

can be divided into 3 phases:

| 1. |

Discussion

of the conclusions |

| 2. |

Constructive

plan |

| 3. |

Parting |

Discussion of the conclusions

has more than one function: a "balance sheet" created initially.

It should make it clear to both partners what has been achieved by the

discussion. It is just as important to describe what has not been

achieved, as further discussion will depend on this, as well as the further

steps which are necessary. As at the start of the conversation, an internal

and external recognition of the other's position is once again necessary,

and should be actively sought. Summarizing at the end of the discussion

has an important control function; it reveals whether the discussion was

based on mutual reality. One objective of the summary is to round off the

discussion psychologically. Discussions which do not have recognizable

conclusions and are open-ended leave both discussion partners with a feeling

of emptiness and uncertainty. On the other hand, discussions from which

conclusions can be drawn give both parties a feeling that they have had

a quantifiable success in their discussion of a problem, that the contract

between them works, and that it is worth-while to have a discussion. The

best motivation for further discussions between doctor and patients is

a successful previous discussion.

The summary of the discussion

is a condition for the "constructive plan", which includes the following

points:

| • |

Prescriptions,

advice, suggestions, and encouragement for the patient |

| • |

Indications and

help as to how the "therapy" can be achieved |

| • |

Possibly a further

appointment |

Of course the concept of

a discussion cannot as a whole apply in every situation of daily clinical

practice (emergency situations, conversations with patients who are not

able to discuss). However wherever discussion serves as a decisive instrument

for dealing with and solving problems and conflicts, the highest degree

of efficiency is achieved with a formal, structured discussion which

is closed as regards content and subject matter.

| top |

|

| previous page |

|

| next page |

|

|

|

Linus

Geisler: Doctor and patient - a partnership through dialogue

|

|

©

Pharma Verlag Frankfurt/Germany, 1991

|

|

URL

of this page: http://www.linus-geisler.de/dp/dp11_dynamics.html

|

|