Discussion techniques

- General principles

| One can't not communicate. |

| Watzlawick |

| 1. |

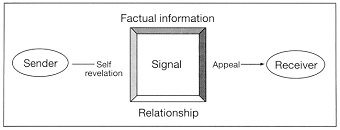

Factual

content (information) |

| 2. |

Self-revelation |

| 3. |

Relationship

(contact) |

| 4. |

Appeal |

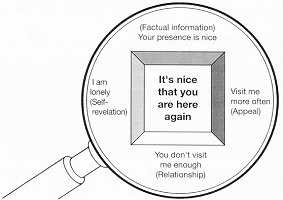

A simple example from daily

life can be used to explain this. The mother greets her son, who does not

often visit her, with the words: "It's nice that you're here again!"

Breaking down the signal

soon shows that there is really more than one message hidden in the sentence.

The first message explains

the facts. The fact that you are here is good. We immediately sense

however that this sentence contains more than a simple statement.

The 4 messages of a signal

(modif. from Schulz von Thun)

The 4 messages of the

signal: "It's nice that you 're here again" under the magnifying glass

of the communication psychologist (modif. from Schulz von Thun)

For example, it says something

about the mother who is sending the signal. The mother is speaking from

the heart about her feelings with the sentence: "It's nice that you're

here again." She is letting it be known that she has missed her son, that

she wanted to see him, and that she is pleased to see him again now. She

is letting it be known how she feels. This self-revelation is the

second

message in the signal.

The third message

says something about the relationship of the son to the mother.

This message usually contains two different messages: the first expresses

what the sender expects from the receiver, and the second, what the relationship

(contact) is between the sender and receiver. The example "It's nice that

you're here again" has an unmistakably critical undertone. The mother also

wants to say: "You don't take enough care of me". By doing this, she says

something about the son, as receiver of the report. At the same time, however,

this sentence also implies something about the closeness and the trust

of the relationship between herself and her son.

The fourth message hidden

in this sentence contains a clear appeal: the mother would like

to use the sentence to express the wish: "You should visit me more often!"

Whenever we speak with one

another, we must be aware that the signals that we give to one another

contain several concurrent messages, which can be of very different weight.

Also the message which appears to be the most important (usually the information)

may not be the most important at all.

This gets even more complicated

by the fact that sender and receiver believe different messages of the

signal report to be the most important for them. It can for example happen

that the receiver believes that the factual information is the most decisive,

but the sender is much more interested in the appeal or the relationship.

It is clear that extensive misunderstandings can develop between

the two, even though the signal which has been sent seems completely clear

and unmistakable.

It may be that the son in

the example given above cheerfully accepts that his mother is pleased to

see him, but no more than that, and therefore doesn't bother to visit her

more often in the future. This signal would then have been unsatisfactory

for the mother, because her son had not "understood" the three messages

which were of more importance to her (her feeling of loneliness, her mild

criticism of his behaviour and her appeal that he should visit her more

often).

A basic fact of communications

can be deduced from this: there are usually 4 things that happen when speaking:

| 1. |

When

I speak, I share a fact —> information. |

| 2. |

When I speak,

I also say something about myself —> self-revelation. |

| 3. |

When I speak,

I tell the other person what I think of him and how we relate to one another

—> relationship. |

| 4. |

When I speak, I seek to

have an influence on the other —> appeal. |

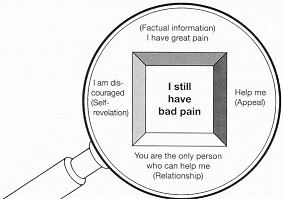

Another example from daily

practice can be used to clearly demonstrate the various messages. During

the morning ward round, the patient says to the doctor: "I still have bad

pain."

Breakdown of the signal:

"I still have bad pain" under the magnifying glass of the communication

psychologist (modif. from Schulz von Thun)

It is not obvious that this

apparently simple statement contains several messages: Everybody understands

the message "I have bad pain" (factual content or information). The second

message is one about the speaker herself (self-revelation). We could presume

that the patient would like to express that she is disappointed about the

experience she has had so far with her treatment, perhaps also losing courage

or feeling confused. The fact that she is approaching the doctor says something

about her relationship with the doctor who is treating her. This is something

like: "I am telling you that I have bad pain, because you are the only

one who can do something about it." However in this message is also something

about her attitude to the doctor: "I am approaching you, because I trust

you." The relationship message therefore not only contains a statement

about what she thinks of him, but also how she relates to him. One cannot

miss the 4th message, the appeal: "You should help me!"

This means that when somebody

speaks to me and I would like to grasp all of the messages of this

statement, it works best if I answer the following 4 questions:

| 1. |

What

is the factual content of the report? |

| 2. |

What is this

telling me about the other person? |

| 3. |

What does the

other person want me to know about myself and about our relationship? |

| 4. |

What does he want to achieve? |

| top |

|

|

Anatomy of the signal

The signal in interpersonal

communication is the sum of the messages, which the sender sends across

to the receiver. It is a "complete many-faceted packet, including both

verbal and nonverbal components" (F. Schulz von Thun).

The extent of this

signal can vary considerably, and there does not have to be a form correlation

between the extent and the amount of information it contains. For example

the information contained in the one word: "Help!" shouted by a drowning

man is far greater than that in a page of a circular letter covered with

words from a German electricity company, announcing in effect, that there

will be a small increase in the price of electricity in the following year.

Even silence (as a

particular sort of not speaking) is a form of communication. Silence is

not just "not speaking", but can involve consciously refraining from to

speaking, even though I should speak or somebody is expecting it from me.

This is the extreme of the basic principle of Watzlawick (1969) summed

up as: "One can't not communicate".

The message given by silence

is inevitably very difficult for the receiver to interpret as it can mean

so many things. How should one interpret the patient who, when asked how

he is, turns towards the wall and does not reply. Perhaps the self-revelation

part of the message is: "I feel so sick that I can't even say it". The

relationship part of the message is perhaps: "You are not the person that

I want to talk to about it", or "I don't trust you", or "I am so disappointed

with results of treatment so far, that I don't want to tell you how I feel".

The appeal is probably: "Leave me alone!". "Don't talk to me!".

In order to understand the

message, it is important to determine whether it contains an implicit

message as well as the explicit one. Something is expressed directly

with the explicit message, whereas the implicit message expresses

it indirectly. In addition, this is made more complicated by the fact that

there are explicit messages which may be actual or apparent.

For example, the explicit

message: "I'm going to bed now" cannot be misunderstood. The signal: "It's

nearly midnight" probably contains the same message, namely "I would like

to go to bed". Perhaps the receiver took this at face value, whereas the

sender possibly would like to express something completely different i.

e. "It's is nearly midnight, but I am working so well that I want to carry

on".

All messages in a

report can be explicit or implicit, which means that there is a great danger

of misunderstandings in the field of implicit messages. It can be very

instructive to examine any everyday conversation for the implicit and explicit

messages that it contains. Usually it will be found that the proportion

of implicit messages is much higher than one would expect.

One of the basic abilities

in successful communication is to determine which is the true major

message of a signal. Is it factual information which has been expressed

or described, or is the real request hidden in the implicit message?

Not recognizing implicit

messages in discussions between doctors and patients can lead to profound

disorders of communication. The patient who says: "I get such a bitter

taste in the mouth from the red pills" could be taken as a purely explicit

message with a clear factual content (subjective drug intolerance). The

implicit messages, which this report (probably) contains as well or even

first and foremost are more difficult to identify. Perhaps the patient

was trying to say: "I think medicines are poisonous", or "I don't want

to take these tablets any more, as they don't suit me". "I doubt if these

are the right tablets for me", "Perhaps these tablets taste so bad because

the diagnosis is not correct", "I don't really believe that your treatment

will work", "I don't want you to treat me" or "Nothing can help me now!".

What possibilities are there

to determine whether a signal contains implicit messages?

One of the basic prerequisites

is active listening (see Chapter on this subject  ).

A further way is that of systematically listening out for implicit messages:

this means putting out a "second internal antenna" to pick up the implicit

messages of the signal. In other words, it is a matter of consciously remembering

that a high proportion of signals contain implicit messages along with

the explicit message. The third method is a very careful observation of

non-verbal parts of the signal, which involves the analysis of movements,

gesticulations and phonetics. ).

A further way is that of systematically listening out for implicit messages:

this means putting out a "second internal antenna" to pick up the implicit

messages of the signal. In other words, it is a matter of consciously remembering

that a high proportion of signals contain implicit messages along with

the explicit message. The third method is a very careful observation of

non-verbal parts of the signal, which involves the analysis of movements,

gesticulations and phonetics.

It is the non-verbal components

of the signal which "qualify" the messages. If there is congruence

between them and they both point in the same direction, the report is "true".

There are contradictions between verbal and non-verbal messages in an incongruous

report.

For example: the young girl

who turns her cheek away from her lover's kiss with the words: "No, because

I don't love you" is sending a congruous signal. However an incongruous

signal is sent by a cyclist after a fall from his bike, who when asked

if he is alright replies: "Life is wonderful" with pain written all over

his face.

Unfortunately it is not always

as easy to spot congruence and (what is far more important) incongruent

as in these examples. The contradiction between verbal and non-verbal parts

of a signal can be relatively small and may not reveal the full extent

of the incongruence.

| top |

|

|

Metacommunication

It is inevitable that communication

always runs on two levels: that of the actual communication and on the

level of metacommunication. The phenomenon of metacommunication

again clearly shows just how complicated the course of sending information

between people has become.

Metacommunication means communication

about communication, or "to unravel the way in which we deal with each

other and about the way in which the report we sent is meant, as well as

sorting out the signal we receive, and how we react." (F. Schulz von Thun).

Metacommunication can also

run explicitly or implicitly. In the true sense of the word, metacommunication

is explicit communication. I. Langer used a picture to try to make the

concept of metacommunication easier to understand. The discussion partners

agree to move to a hillock to get away from the hustle in which they were

tangled up. At this vantage point, sender and receiver make the manner

in which they are dealing with each other the subject of their discussion.

Explicit metacommunication which is used economically can be an excellent

method of re-establishing mutual understanding by consciously analyzing

and talking about the factors which are disturbing conversation. Parallel

to the communication on the level of a signal, there is always communication

on the meta-level in the sense of implicit metacommunication. This is the

"this is meant" part of every signal. Thus the messages at both levels

"qualify" each other. J. Haley (1978) differentiated 4 possibilities by

which the signal could be qualified in either a congruent or incongruent

way: qualification by context, the way of formulation, by movements and

gesticulation as well as the tone of voice.

When the Countess in Tolstoi's

"Anna Karenina" dismisses the young Ljewin in a cool and dry tone to the

words: "We shall be pleased to see you", then such parting is experienced

by the one leaving as a classical example of implicit metacommunication.

He was aware that the factual content of the signal ("We shall be pleased

...") was a polite but empty phrase, as the true message was expressed

by the tone of voice. The correct decoding of a signal is also bound up

with the ability to recognize the metacommunicative content. The nature

of implicit metacommunication can be summed up briefly as: "When I send

a signal, I also send (whether I want to or not) a message about how this

signal is meant to be received" (F. Schulz von Thun).

| top |

|

|

Hearing the signal

It is almost a coincidence if

the sender correctly codes the signal to say what he would like to say

and if the receiver in turn decodes it as the sender meant it, even though

it is presumed to happen all the time in the course of communication between

people.

The mere recognition that

each signal contains 4 messages, which can be in turn either congruent

or incongruent, explicit or implicit, and that there is metacommunication

in addition, raises reasonable doubt whether talking to one another and

understanding one another is as simple as it is made out to be.

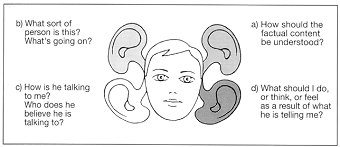

The complexity of this procedure

becomes even more obvious when we realize that the correct decoding of

the signal by the receiver means that he has to have a particular ear for

each of the messages of a signal; in other words, he has to have "four

ears". He needs a factual ear, a relationship ear, a self-revelation ear

and finally an appeal ear (see figure).

Correct understanding

requires the receiver to have "4 ears" a) Factual ear b) self-revelation

ear c) relationship ear d) appeal ear (mod. from F. Schulz von Thun)

The factual ear checks

the signal with the question: "How is the factual information to be understood?".

The self-revelation ear would like to hear something about the person

opposite: "What sort of person is this?" The relationship ear (which

is often very sensitive) is used by the receiver to ask himself: "What

relationship does he think he has with me? What does he think of me?" And

with the appeal ear, he poses the question: "What does the sender

want to achieve?"

The completely different

ways in which the signal can be "taken" are shown in the following simple

question, asked by a husband during breakfast: "Where did you buy this

bacon?"

If the wife receives this

signal with the factual ear, she will reply: "In the supermarket". If she

hears it with the excessively sensitive relationship ear, she will take

the question as a criticism of her housekeeping, and reply: "You can eat

breakfast in the canteen at work if you like". However if she picks it

up with self-revelation ear, then this might be one more confirmation of

her husband's nosiness, and release the reaction: "Do you have to know

everything?". If the wife understands this as an appeal, she would reply:

"I can buy it from the butcher instead of the supermarket next time".

Obviously the receiver receives

all 4 messages of the signal at the same moment, filters them to a greater

or lesser extent, and hears with more than one ear. One of the fundamental

problems of communication is that the reaction of the receiver

to the signal depends on whether he is aware or unaware that he is more

likely to hear with one ear.

The trained receiver must

have the ability to receive the signal that the sender is transmitting

with all 4 ears. Major disorders of communication can arise if he only

hears with one "ear" (for example, with the factual ear or the relationship

ear, because he has consciously or unconsciously closed the other ears).

For example, men who tend

to take up technical or academic careers choose to hear with the factual

ear, and receive no other message apart from the factual content. On the

other hand, marriage partners, particularly when they are under stress,

only receive in the relationship ear, and are unable to pick up a factual

statement. They are "lying in wait for one another".

A well-trained self-revelation

ear is very important for the doctor, as this is his diagnostic

ear. He uses this to sift out whatever can lead him to understand his

patient. Even when the patient has an emotional outburst, his self-revelation

ear allows him to have a better attitude to the patient than if he were

using only his relationship ear.

Of course this does not mean

that the doctor should "switch off" the relationship ear completely, and

listen only with the self-revelation ear and the factual ear, as this would

result in the patient being observed as a diagnostic object, and rob the

doctor of the ability to be affected or involved.

Schulz von Thun has pointed

out the additional danger of "psychologization", which results if

the self-revelation ear alone is used (or rather misused). The factual

content of a signal is ignored, and the signal only examined under the

aspect of what kind of person is hidden behind this signal. The receiver

judges all of the statements of the other under the motto: "He only says

that because he is made up in that way."

A well-trained self-revelation

ear is vital for active listening. It allows us the possibility

of sensing the thought and affective world of the other, and not to regard

him as just an object, or to continue to judge him from a human point of

view.

The appeal ear also

plays an important role in discussions between doctors and patients. If

the appeal ear is not tuned in, many requests, desires, hopes and expectations

of our patients would be ignored, as analysis of the factual content of

their signals would leave them unheard.

A particularly ominous example

is that of "overhearing" (in the sense of "overlooking") the intent to

commit suicide. This may be considered to be the final appeal to those

around, and can probably only be picked up with a very finely-tuned appeal

ear, which warns us about cries for help made with faintly-transmitted

signals during the course of discussion.

The appeal ear can also be

used diagnostically when we need to review, and ask about the objective

of a statement or way of behaving. It was Alfred Adler who employed the

method of the "what purpose does it serve" question, such as for example:

"What advantage do you derive from your migraine?"

If a problem in communication

has arisen, the receiver should go through the following check-list:

1. What are the messages

in the signal?

2. Which was the main

message?

3. Does the signal also

contain implicit messages?

4. Was the signal congruent

or incongruent?

5. What was expressed on

the level of metacommunication? (the "that-is-what-is-meant" part

of the signal)

6. Have I picked up the

signal with 4 ears or with only one? |

|

The content of the signal which

is transmitted by the sender, is not (as in a postal package) identical

to the content which "gets to" the receiver.

What somebody says is simply

not identical to that which the other hears. We call it misunderstanding,

and tend to look for blame instead of for the cause. Understanding, as

well as misunderstanding, are part of the nature of every communication.

| The knowledge that each

signal contains various messages, as well as the ability to receive signals

with 4 ears, are the best guarantee that misunderstandings can be minimized

in communication between people. |

|

| top |

|

| previous page |

|

| next page |

|

|

|

Linus

Geisler: Doctor and patient - a partnership through dialogue

|

|

©

Pharma Verlag Frankfurt/Germany, 1991

|

|

URL

of this page: http://www.linus-geisler.de/dp/dp06_speech.html

|

|